Getting Started

When you have diabetes you may often be encouraged to do some exercise. So why is exercise particularly recommended for you? Well, there is no doubt that regular physical exercise can improve your health and well being and helps control your weight but dont forget it can be fun too!

As diabetes is largely a condition where you manage your day-to-day treatment yourself, you need to understand what happens to the body during exercise. This will help you to optimise your blood glucose control, improve your performance, avoid hypoglycaemia and ultimately tailor a plan to suit your training.

Having diabetes should not be a barrier to exercise; instead remember that exercise can be both beneficial and enjoyable. Thought and planning is needed to optimise your blood glucose control, and blood glucose needs to be tested before and following exercise. Your food intake may need to be altered to reduce the risk of hypoglycaemia.

This information is for people with Type 1 diabetes so that you can safely and effectively manage blood sugars before, during and after exercise. The instructions given here are designed as a starting point and will need modifying for each person and for each exercise regime that is being undertaken by that person.

To exercise safely you will need to learn about a number of things.

• Be prepared to monitor their blood sugars regularly

• Know how to treat hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia

• Be able to grade the intensity of exercise

• Understand how different exercises affect blood glucose

• Have a knowledge of carbohydrate counting

• Have some idea of how sensitive they are to insulin

• Be able to do basic maths

• Know how to treat hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia

• Be able to grade the intensity of exercise

• Understand how different exercises affect blood glucose

• Have a knowledge of carbohydrate counting

• Have some idea of how sensitive they are to insulin

• Be able to do basic maths

Exercise

Definition

Exercise can be defined as physical activity that is planned, structured, and repetitive for the purpose of conditioning any part of the body. Exercise is used to improve health, maintain fitness and is important as a means of physical rehabilitation.

Exercise can be defined as physical activity that is planned, structured, and repetitive for the purpose of conditioning any part of the body. Exercise is used to improve health, maintain fitness and is important as a means of physical rehabilitation.

Intensity of exercise

Exercise intensity refers to how much work is being done when exercising. The intensity has an effect on what fuel the body uses (see later section) and what kind of adaptations the body makes after exercise (i.e., the training effect). Intensity can be measured a number of ways but the 2 most common are;

Exercise intensity refers to how much work is being done when exercising. The intensity has an effect on what fuel the body uses (see later section) and what kind of adaptations the body makes after exercise (i.e., the training effect). Intensity can be measured a number of ways but the 2 most common are;

Percentage of maximum heart rate (figure 1)

The maximum heart rate (HRmax) is the highest heart rate an individual can safely achieve through exercise stress, and depends on age. The most accurate way of measuring HRmax is via a cardiac stress test. In such a test, the subject exercises while being monitored by an ECG. Doing such a test is expensive and for general purposes, people instead typically use a formula to estimate their individual maximum heart rate. The best formula for calculating this is HRmax = 208 − (0.7 × age).

The maximum heart rate (HRmax) is the highest heart rate an individual can safely achieve through exercise stress, and depends on age. The most accurate way of measuring HRmax is via a cardiac stress test. In such a test, the subject exercises while being monitored by an ECG. Doing such a test is expensive and for general purposes, people instead typically use a formula to estimate their individual maximum heart rate. The best formula for calculating this is HRmax = 208 − (0.7 × age).

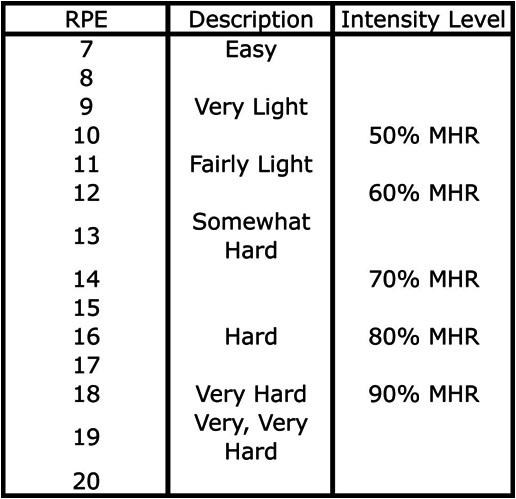

Borg scale of perceived exercise

Aerobic energy system

The term ‘aerobic’ in this context refers to the fact that oxygen is required in the process whereby carbohydrates and fats are oxidised (burned) completely to make ATP (the energy currency of all cells). Typically endurance sports require energy from predominantly aerobic sources.

Anaerobic exercise system

The term anaerobic in this context refers to the fact that energy is being produced without the need for oxygen. As the intensity of exercise increases there is an increasing contribution from anaerobic sources and a decreasing contribution from aerobic sources. In general the more anaerobic the activity the more carbohydrate that is used and the more aerobic the activity the more carbohydrate that is used. The higher the intensity of exercise the more glucose is burned and the greater amount of a metabolic intermediary, lactate is produced. Lactate used to be thought of as a waste product but we now know that it is a carbohydrate which also makes a huge contribution as a fuel. Indeed when exercise occurs at an intensity of greater than 50% of an individual’s maximum possible exercise intensity more than 50% of the fuel is lactate. And much of this lactate is a fuel which is used to a large degree by heart muscle.’

Training can increase both your capacity for aerobic exercise and your tolerance of the lactate produced during anaerobic exercise.

Training can increase both your capacity for aerobic exercise and your tolerance of the lactate produced during anaerobic exercise.

Exercise and diabetes, what happens?

When you have diabetes your body is unable to control blood glucose levels and, during exercise, your blood glucose can rise or fall, depending upon the type of exercise you take:

- Anaerobic exercise

during short periods of anaerobic exercise, or exercise with short burst of activity, your glucose may rise;

during short periods of anaerobic exercise, or exercise with short burst of activity, your glucose may rise;

- Aerobic exercise

in contrast, glucose levels generally fall with prolonged aerobic exercise. Hypoglycaemia after exercise can also be a problem.

in contrast, glucose levels generally fall with prolonged aerobic exercise. Hypoglycaemia after exercise can also be a problem.

Which Exercise is Best for Me?

Whilst any exercise is beneficial, you should choose an activity that best meets your goals and is safe for you to do.

Prolonged aerobic exercise at low intensity is the best for weight control. Any antigravity exercise such as running, or using a treadmill with an incline in a gym for 40 minutes at a time will help burn fat. Cycling is also good, but swimming is less effective as your body weight is supported by water.

Be careful if you have diabetic foot problems. Running and treadmill work are not recommended for you. Also, if you have heart, eye or blood pressure problems, advice should be sought prior to starting your exercise program.

Planning for Exercise

It makes sense to plan for exercise in advance rather than to take extra glucose later to deal with hypoglycaemia. Here are a few pointers:

· Before starting any new exercise regime discuss it with your healthcare professional. In particular discuss with them how to adjust your pre exercise insulin or diabetes tablets.

· You need to think about the timing, duration and intensity of the exercise so you can plan your diabetes treatment, food intake and blood glucose testing.

· Test your blood glucose regularly during and following exercise and immediately take steps to correct falling blood glucose.

· Glucose (30-60 grams per hour) in the form of a drink or as tablets (e.g. Dextrosol) can help protect you against hypoglycaemia.

· You need to think about the timing, duration and intensity of the exercise so you can plan your diabetes treatment, food intake and blood glucose testing.

· Test your blood glucose regularly during and following exercise and immediately take steps to correct falling blood glucose.

· Glucose (30-60 grams per hour) in the form of a drink or as tablets (e.g. Dextrosol) can help protect you against hypoglycaemia.